Mermaid Tales and Fish Fatales

Insight into the original "Little Mermaid," monstrous Mxes, misters, and mistresses of the sea from Assyria to Japan, plus immortal jellyfish and Columbus sightings

The Cauldron is a reader-supported publication featuring curious occult history and mythology. Visit pick-your-potions.com to learn more about witchy author, teacher, and mixologist Lindsay Merbaum.

Special thanks to photographer Jose de los Reyes for the spellbinding art shared in this post!

As a kid, I was game to swim anywhere, anytime.

If someone let me in their pool, I believed I undulated through it like Daryl Hannah in Splash (which I just discovered is on Disney+, btw). This was the 90’s: I’d seen Disney’s The Little Mermaid too, of course. I liked Ursula the sea witch best. (Is Ursula a mermaid-witch? An homage to famed drag queen Divine, Ursula has cephalopod appendages instead of a fish tail, but her top half is human, just like Ariel. She sings, too.) I was likewise enchanted by the selkie’s longing, and the bird-footed sirens’ song of death. What a power, to compel a man to drown himself.

Nowadays, scores of adults lounge poolside in full-scale mermaid tails, the best of which are custom made. Mermaiding is a serious business, both an art—some would say a kind of drag performance—and a specialized, high-risk sport. The 2023 Netflix documentary MerPeople provides insight into the history and culture of professional mermaids. (Anecdotally, I have met some career mermaids who felt this doc misrepresented and trivialized their work.)

Then there’s Coney Island’s famed Mermaid Parade, founded in 1983, which I got to attend as a college student, when it seemed like just another wonderfully strange quirk of NYC, like a nightclub in a church, or a full-on Halloween. The Mermaid Parade is a kitschy, appropriately freaky, queer-friendly pageant, with floats and revelry, where a King Neptune and Queen Mermaid are crowned, and crowds show up as all kinds of sea creatures. There’s music, dancing, clamshell bikinis and colorful wigs. Hundreds of thousands turn out for it every year.

It’s easy to forget that the mermaid is a monster.

Their existence begs the question: what else did the seas birth?

The mermaid merges our desire and fear: a lust for the unknown, the thrill of risking death. They live in the lifesource, the great abyss—but you can’t stay there among them unless you’re dead. They look like a person, or a familiar animal—a seal, or a monkey, perhaps. Maybe they’ll save you, or eat you. Or break your heart.

There were many sea deities in ancient Mesopotamia, from Ninhursag to Tiamat. The Sumerian god of wisdom, Enki, was sometimes depicted with a fish tail.

But the first mermaid appears in Assyrian mythology around 1000 BCE: ashamed of having killed her lover, the goddess Atargatis throws herself in a lake and swims away.

Via trade routes, the mythology spread around the Mediterranean. The seafaring Carthaginians were influenced by neighboring Phoenicians, resulting in the only water djinn, the Tunisian jnoun of the sea.

In Legends of the Fire Spirits, Robert Lebling characterizes the djinn as ubiquitous throughout the Middle East, parts of Asia (Indonesia, Bangladesh, and Pakistan), and regions of Africa, including Morocco, Tanzania, Nigeria, and Tunisia. Basically anywhere Islam predominates. There are different types and classes of djinn—including good and bad djinn—whose origins and attributes depend upon the region. For example, the Egyptian djinn echo ancient Egyptian theology, and Persian djinn differ from Arabic djinn, and there are djinn of each major faith.

Tunisia is unique for hosting djinn of the sea, called jnoun. Jnoun have a human torso and the tail of a fish. Many sea jnoun sightings occur, unsurprisingly, among fishermen.

The singing sirens of ancient Greek mythology, who lured sailors to their deaths, had legs.

In the Odyssey, Odysseus must sail through treacherous siren territory. Originally, the sirens had bird-bodies, which suits their beautiful voices. Now, their beauty has become literal: Odysseus expects to be lured by attractive women. He has his men plug their ears with wax, but leaves his own ear canals unstoppered. Tied up so he can’t dive overboard, Odysseus is the only one who gets to experience the call of the sirens. It takes hold of him, of course—he’s just a man—and he struggles to free himself. This is one of many instances where Odysseus, supposedly so keen to get home that it’s the motivation for his entire narrative, takes a huge gamble on his own life.

By the ninth century, the siren had grown a fishtail and officially become a mermaid. Six hundred or so years later, Christopher Columbus himself claimed he saw three mermaids near what is now known as the Dominican Republic. Columbus was unimpressed by the beauty of these creatures, who were probably manatees, a favorite among Florida tourists.

The Turritopsis dohrnii jellyfish is immortal: if it’s hurt or starving, it turns into a polyp and just starts life over again. Respawn!

The original little mermaid suffers a great deal.

This is the story I read as a child: the sea-witch cuts out the young mermaid’s tongue, rendering the girl mute. Many queer scholars view this as a surgical sacrifice. The mermaid downs a potion and now she has legs—a reversal of the siren’s evolution—but every step is like walking on swords. (Sidenote: in European folklore, terrible things happen to women’s feet. Cinderella’s step-sisters slice off parts of theirs, and Snow White’s stepmother “dances” to death in hot iron “shoes.” Then there are the red shoes, of course, and others, that compel you to dance.) In the end, the prince leaves her for someone else and the mermaid commits suicide. A number of scholars agree the story is a queer allegory: Andersen wrote it after Edvard Collin, the son of Andersen’s patron, rejected him.

JStor Daily points to the relationship between the ocean and queer outsiders, like the famous queer pirate lovers Anne Bonny and Mary Read. The sea is rife with danger, but it’s also another world, where the laws of the land—the domain of men—don’t apply.

Aphrodite, the Greek goddess of love, is a descendant of the Sumerian goddess Inanna, who became Ishtar and Astarte. The story of Aphrodite’s birth is a muddled one, though it appears she forms from the severed genitals of Uranus, the sky, when he is castrated by his son Cronus (father of Zeus). Aphrodite emerges, full-sized, from the waves, the sea both her mother and father. Her name means “born from sea foam.”

Melusine may be best known as the two-tailed mermaid on the Starbucks’ logo, though she’s also depicted with a single snake tail, or a dragon’s body.

Another possible inspiration for the story we know as “The Little Mermaid,” there are many versions of Melusine’s legend, but one of the most widely known appears in a 14th-century French novel by Jean d’Arras. D’Arras describes a young woman whose mother burdens her with a terrible curse: every Saturday, half her body turns into a snake. This goes on until she marries a man with enough respect for boundaries to leave her alone on the sixth day of the week. Melusine has ten sons with her husband Raymondin, and things go along swimmingly for him. Until Raymondin breaks his promise and spies on his wife on a Saturday. For that, Melusine leaves him.

“The Little Mermaid” was first translated into Japanese in the 1910’s.

The tale became known as Ningo Hime—“Ningyo Princess.” But ningyo and “mermaids” are not sea cucumbers to sea cucumbers. The ningyo—literally human fish—refers to a range of nymphs and hybrid ocean creatures. Some are closer in appearance and demeanor to Ursula than Ariel. Philip Hayward, author of Scaled for Success, explains:

While the term ningyo is often translated into English language as 'mermaid' (or 'merman', as the term is not gendered), this is misleading in that the creatures originally described and represented in Japan are not the familiar portmanteau form of the Western mermaid, with abrupt delineations between an upper, fully human half and a lower, fully piscine one, but are rather more varied (and often monstrous) piscine-humanoid beings […] other early images have either monkey-like heads or fish-scaled humanoid faces on fish bodies […]

Though tales vary by region, generally the flesh of the ningyo has magical properties. Consuming it grants the eater long-lasting life—as many as 800 years, even. In one story, ningyo flesh is served at a wedding. Though a Buddhist priest takes his portion home, essentially declining to eat it, a young girl tries some, not knowing what it is. She lives to be 800 years old. In that time, she becomes a Buddhist priestess and travels the world. But she has to watch everyone around her die.

When a fisherman catches a ningyo and mercilessly kills it to feed his (presumably hungry) children, the children grow scales, then die. In other cases, a person is transformed into a ningyo as punishment.

Another magical, aquatic being from Japan is the kappa: known for their turtle-like cuteness, lechery, and vampiric behavior, the kappa of Japanese folklore sometimes pull pranks, or drown children. They may also extract livers through the anuses of unsuspecting toilet-goers. Kappa do have a weakness: the tops of their heads serve as wells for magical waters that help maintain their powers. If you can trick them into spilling this water, you’ll have the upper hand and might extract a favor.

Kappa love cucumbers, so bring some along for offerings—or distraction—if you plan on entering their territory.

Mami Wata—Mother Water—is both one and many: a pantheon of water spirits, and a goddess. Half-human, half-fish, Mami Wata is a snake-charmer with long, flowing hair. Mami Wata is a goddess of the African diaspora. She gained notoriety during the 15th century and is worshipped from Senegal to Zambia, as well as in Brazil, the Caribbean, and right here in the US. Capable of cruelty and kindness, she is a protector of children, and a force of destruction.

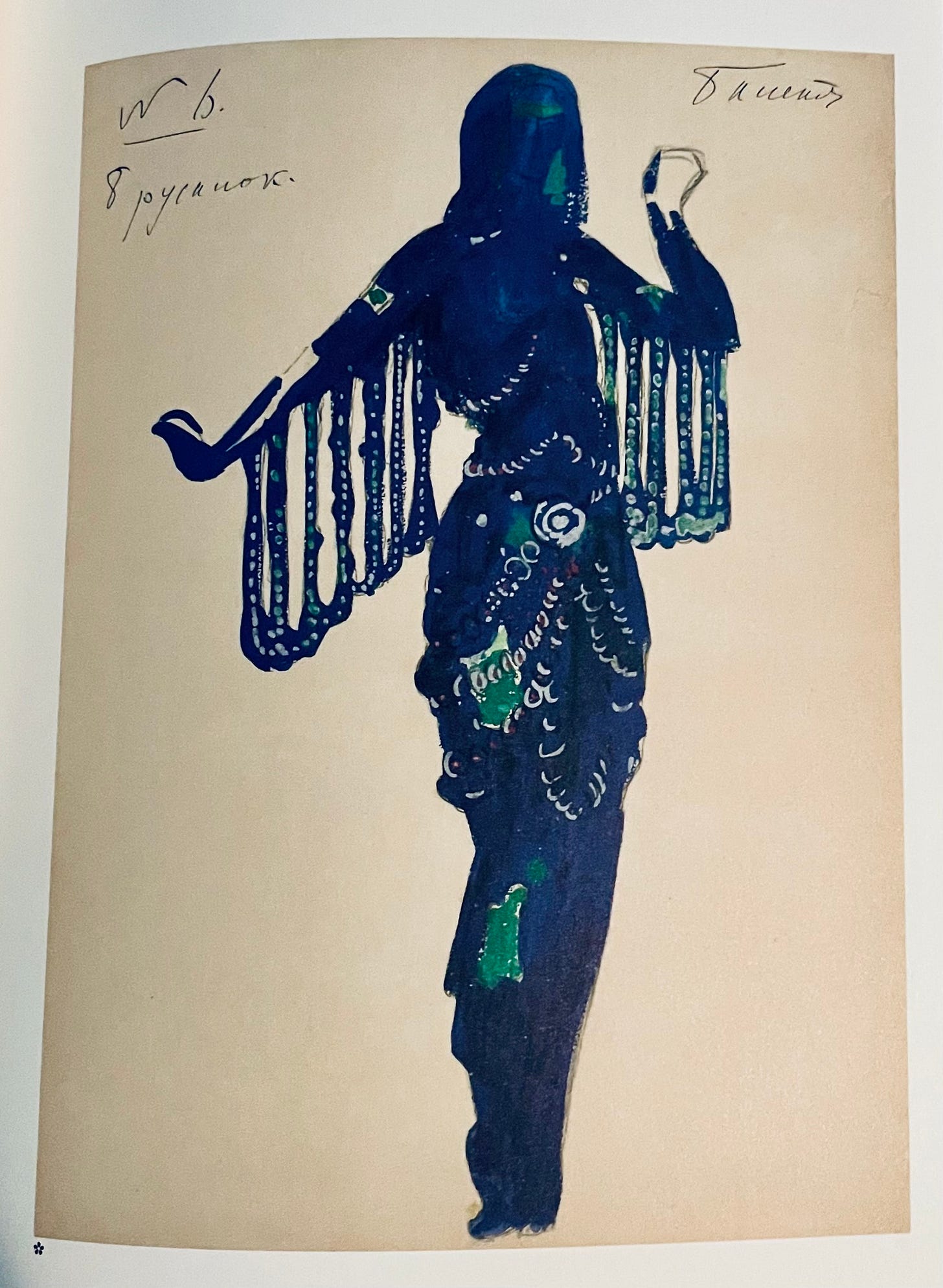

In Slavic mythology, rusalki are freshwater beings transformed from the souls of unbaptized children, or virgins who drowned.

Some sing like sirens, other rusalki are hideous and cruel. Pretty or ugly, they may torture you, drown you in their hair, or tickle you to death.

Until around the 1930’s, rusalki week was celebrated at the beginning of summer, when the nymphs would emerge from the water to sit dripping from willows and birches. Then they danced by moonlight. The grass grew tall wherever the rusalki tread. Those who joined them danced ‘til they died.

Rusalka the opera premiered in Prague in 1901. The story is a familiar one: a water nymph named Rusalka falls in love with a human prince, much to the horror of her father. To be with this man, Rusalka makes a pact with a sea witch. Not only does the nymph sacrifice her voice in the bargain, but the witch warns if she doesn’t achieve her happily ever after, she’ll be damned and the prince will die.

In the early 1800’s, the deep sea was considered utterly uninhabitable. Then, there was a surge of discoveries. Yet, a few hundred years later, at least 80% of the ocean is still unexplored.

What is a mermaid?

A nymph, monster, or sea witch? Gendered or genderless? All of the above? The varied mythology of humanoid sea beings are all, essentially, about shapeshifting. In “Mermaids and Drag Queens: A Queer Look at Mermaiding,” Yuval Avrami explains “[…] the mermaid is non-binary in its essence: she defies binaries and dichotomies by living on sea and above it, being both human and animal, and having a human identity but no human genitalia -an identity not dependent on sex organs.” This inherently resonantes with many trans, nonbinary, and genderqueer identities. Trans author and celebrity Janet Mock writes in Allure:

Like Ariel, I was told I wasn’t a real girl because of my body, and this common struggle to be seen as normal, to just belong, tethered my trans girl self to Ariel’s mermaid girl self. Plus, it didn’t hurt that my childhood heroine was gorgeous — the epitome of femininity — despite struggling to exist in an untraditional form.

For the outsiders, outliers, and other queer folk, myself included, mermaids and other mythical hybrid creatures will always feel familiar—there’s a sense of belonging among the magically monstrous. And a respect for their power, which we hope to see reflected in ourselves.

And this is where the magical hybrid being meets the potent queer witch. Janet Mock had Ariel, I had Divine-inspired Ursula.

Thanks for reading! If you liked this post, please pass it on! And by all means, share your thoughts in the comments. Cheers!

-Lindsay